Steven and Roberta Denning Professor of Finance

Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution

Senior Fellow, Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research

Recent Research

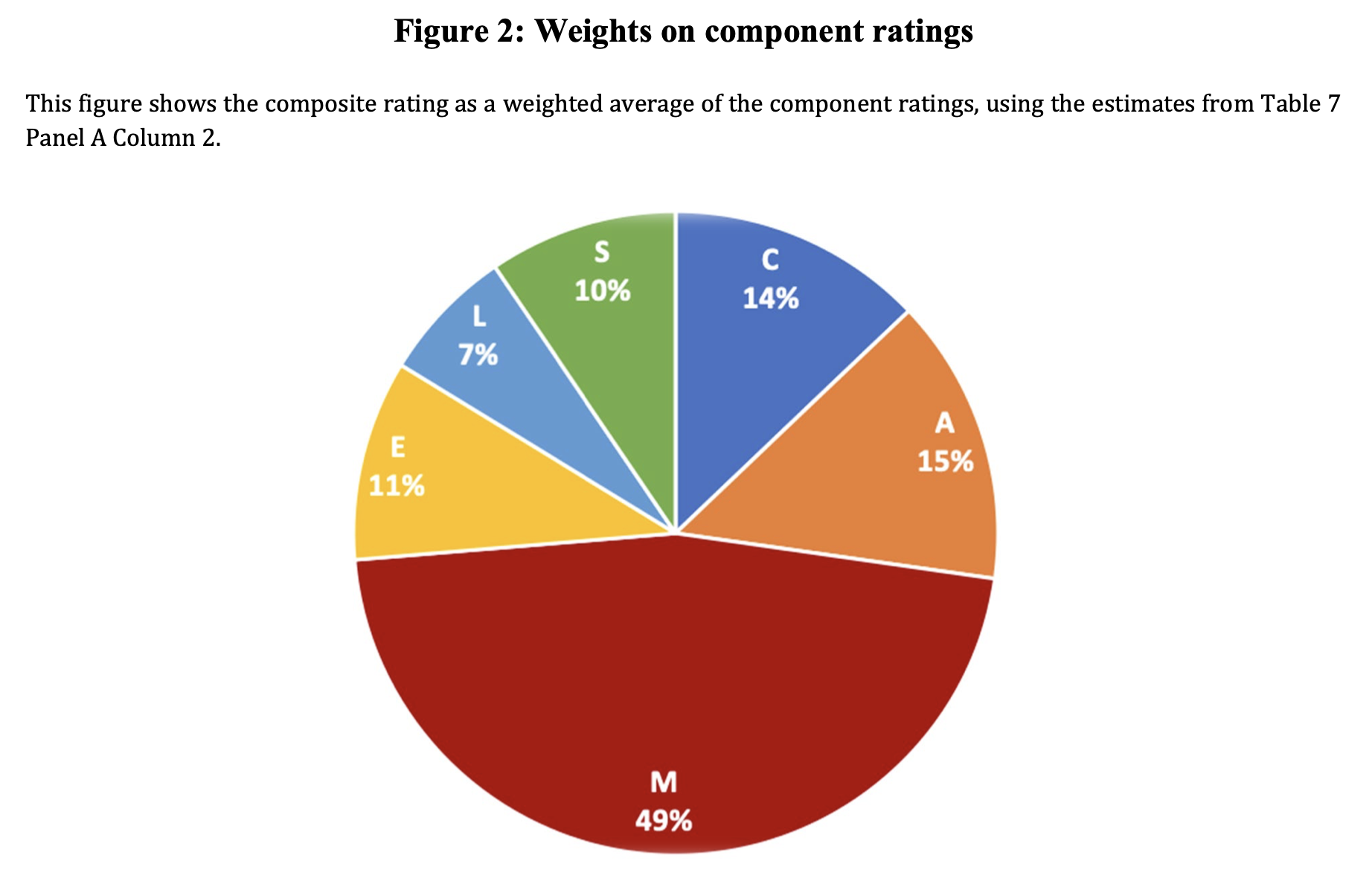

While reliance on human discretion is a pervasive feature of institutional design, human discretion can also introduce costly noise (Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein 2021). We evaluate the consequences, determinants, and trade-offs associated with discretion in high-stake decisions assessing bank safety and soundness. Using detailed data on the supervisory ratings of US banks, we find that professional bank examiners exercise significant personal discretion—their decisions deviate substantially from algorithmic benchmarks and can be predicted by examiner identities, holding bank fundamentals constant. Examiner discretion has a large and persistent causal impact on future bank capitalization and supply of credit, leading to volatility and uncertainty in bank outcomes, and a conservative anticipatory response by banks. We identify a novel source of noise: weights assigned to specific issues. Disagreement in ratings across examiners can be attributed to high average weight (50%) assigned to subjective assessment of banks’ management quality, as well as heterogeneity in weights attached to more objective issues such as capital adequacy. Replacing human discretion with a simple algorithm leads to worse predictions of bank health, while moderate limits on discretion can translate to more informative and less noisy predictions.

(with Buchak, Matvos and Piskorski), 2024

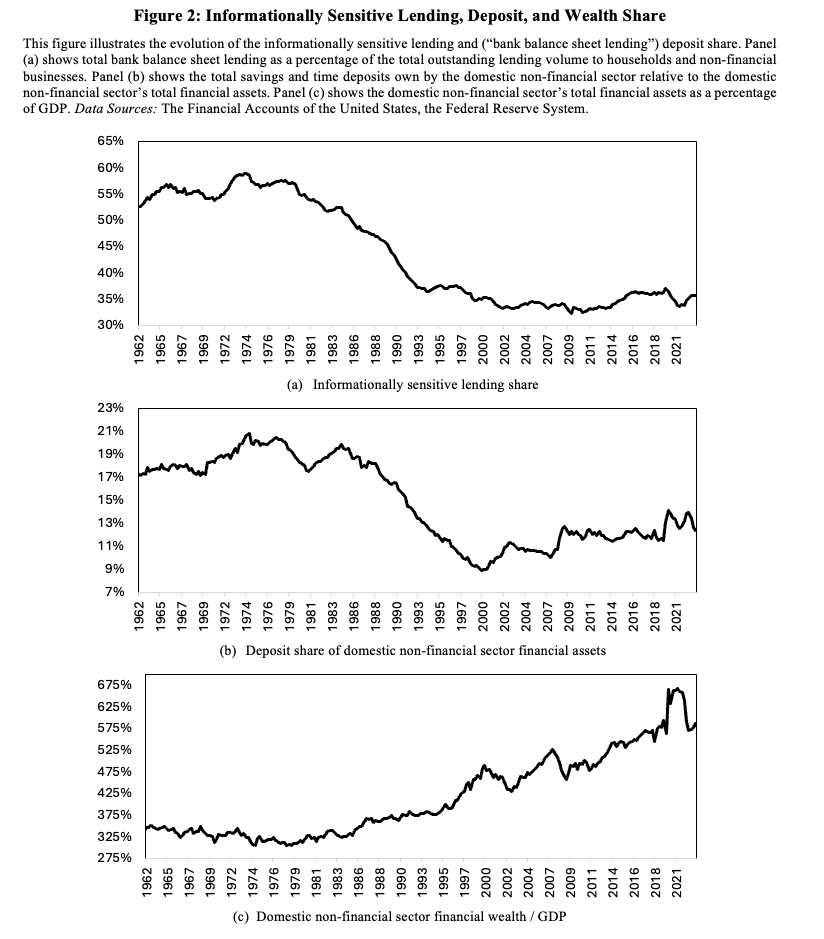

The traditional model of bank-led financial intermediation, where banks issue demandable deposits to savers and make informationally sensitive loans to borrowers, has seen a dramatic decline since 1970s. Instead, private credit is increasingly intermediated through arms-length transactions, such as securitization. This paper documents these trends, explores their causes, and discusses their implications for the financial system and regulation. We document that the balance sheet share of overall private lending has declined from 60% in 1970 to 35% in 2023, while the deposit share of savings has declined from 22% to 13%. Additionally, the share of loans as a percentage of bank assets has fallen from 70% to 55%. We develop a structural model to explore whether technological improvements in securitization, shifts in saver preferences away from deposits, and changes in implicit subsidies and costs of bank activities can explain these shifts. Declines in securitization cost account for changes in aggregate lending quantities. Savers, rather than borrowers, are the main drivers of bank balance sheet size. Implicit banks’ costs and subsidies explain shifting bank balance sheet composition. Together, these forces explain the fall in the overall share of informationally sensitive bank lending in credit intermediation. We conclude by examining how these shifts impact the financial sector’s sensitivity to macroprudential regulation. While raising capital requirements or liquidity requirements decreases lending in both early (1960s) and recent (2020’s) scenarios, the effect is less pronounced in the later period due to the reduced role of bank balance sheets in credit intermediation. The substitution of bank balance sheet loans with debt securities in response to these policies explains why we observe only a fairly modest decline in aggregate lending despite a large contraction of bank balance sheet lending. Overall, we find that the intermediation sector has undergone significant transformation, with implications for macroprudential policy and financial regulation.

(with Jiang, Matvos and Piskorski), 2024

We examine why banks maintain such high financial leverage, with debt financing accounting for about 90% of banks’ assets. To answer this question, we use uniquely assembled data on capital structure decisions of shadow banks that on the asset side conduct very similar business to banks. The shadow bank data provides us with a window into “free market” financing choices of financial intermediaries that unlike banks are lightly regulated and do not have access to insured deposit funding. We demonstrate that shadow banks employ twice the amount of equity capital compared to equivalent banks, with the most significant disparity observed between smaller and mid-size banks. Uninsured leverage, defined as uninsured debt funding to assets, increases with size for both banks and shadow banks while cost of debt declines with size. We rationalize these facts within a calibrated quantitative equilibrium model of intermediation. Our analysis reveals that the primary driver of high leverage among smaller and mid-size banks is their access to insured deposit funding. In the absence of deposit insurance, these banks would maintain a capitalization level at least 25% higher in relative terms than observed in the data. Conversely, deposit insurance plays a comparatively minor role in influencing the financial leverage of the largest banks, where the predominant factor is their capacity to generate money-like deposits. These results suggest a significant scope for the increase of capitalization of smaller and mid-size banks to align their capital structures with their private market counterparts. The aggregate consequences of such increase would be limited, because of reallocation of lending activity from smaller to large banks and to shadow banks.

(with Jiang, Matvos and Piskorski), 2024

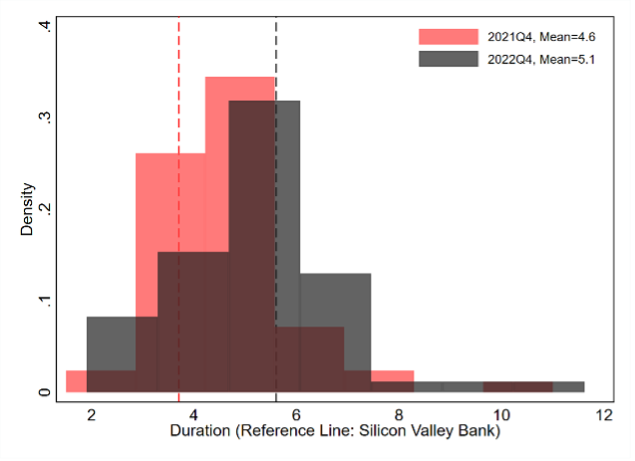

In the face of rising interest rates in 2022, banks mitigated interest rate exposure of the accounting value of their assets but left the vast majority of their long-duration assets exposed to interest rate risk. Data from call reports and SEC filings shows that only 6% of U.S. banking assets used derivatives to hedge their interest rate risk, and even heavy users of derivatives left most assets unhedged. The banks most vulnerable to asset declines and solvency runs decreased existing hedges, focusing on short-term gains but risking further losses if rates rose. Instead of hedging the market value risk of bank asset declines, banks used accounting reclassification to diminish the impact of interest rate increases on book capital. Banks reclassified $1 trillion in securities as held-to-maturity (HTM) which insulated these assets book values from interest rate fluctuations. More vulnerable banks were more likely to reclassify. Extending Jiang et al.’s (2023) solvency bank run model, we show that capital regulation could address run risk by encouraging capital raising, but its effectiveness depends on the regulatory capital definitions and can by eroded by the use of HTM accounting. Including deposit franchise value in regulatory capital calculations without considering run risk could weaken capital regulation’s ability to prevent runs. Our findings have implications for regulatory capital accounting and risk management practices in the banking sector.

(with DeMarzo, Jiang, Krishnamurthy, Matvos and Piskorski), 2023

Summary

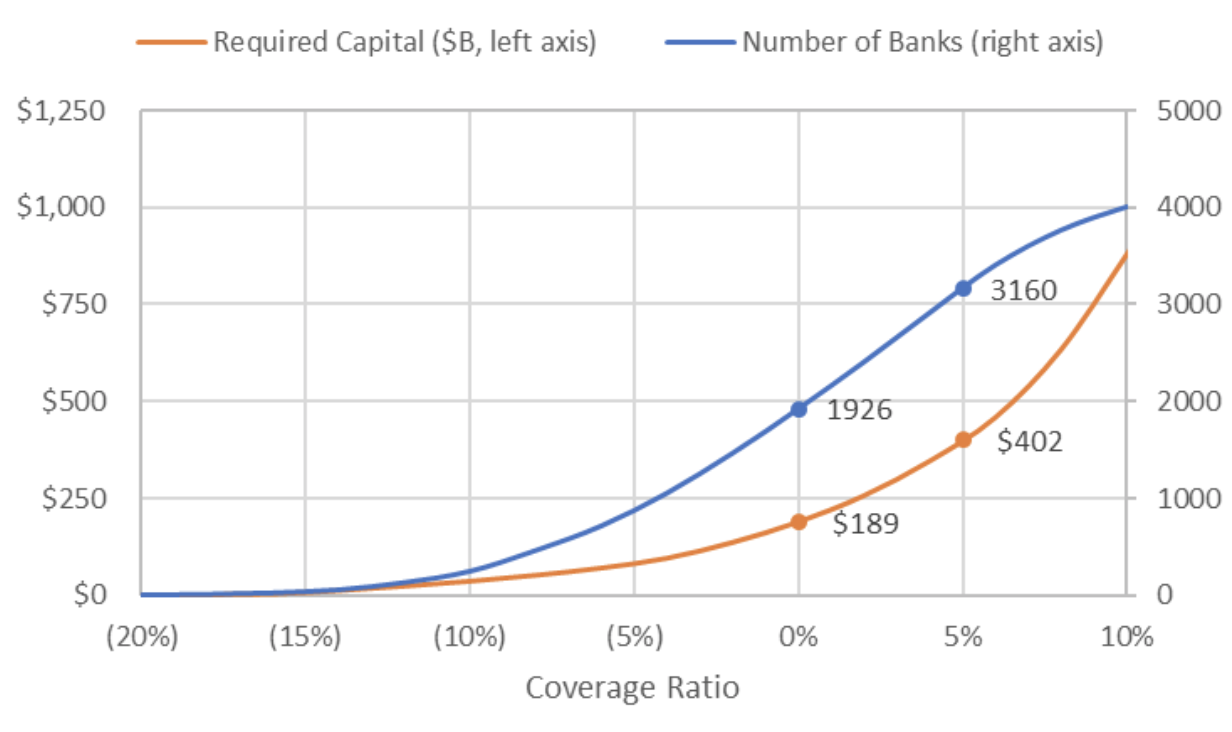

- New economic conditions have led to insolvency concerns across the banking system.

- There are too many banks in this situation to resolve with one-off solutions.

- Government backstops and regulatory forbearance risk a repeat of the S&L crisis.

- Requiring banks to promptly raise equity capital will both reduce fragility and provide a needed market test to identify truly insolvent banks.

- The amount of private capital needed is in the range of $190 to $400 billion.

Selected Data

Financial Advisor Misconduct Statistics based on The Market for Financial Market Misconduct

by Egan, Matvos and Seru,

Journal of Political Economy, 2018

[Data here]